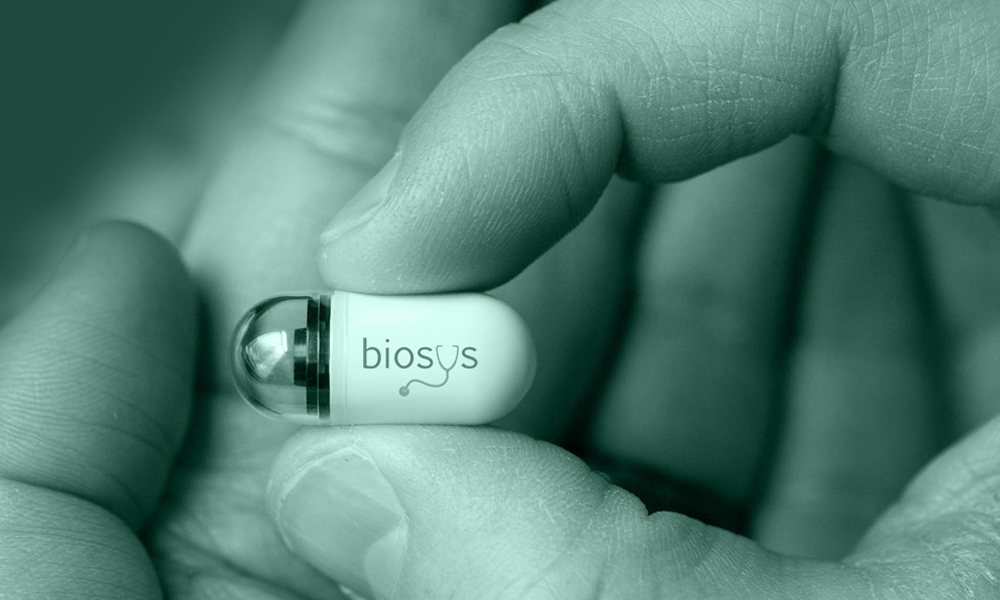

Capsule endoscopy has emerged as a pivotal advancement in gastrointestinal diagnostics, offering a non-invasive alternative to conventional endoscopic techniques. With its expanding clinical indications and growing technological sophistication, its role in routine practice continues to evolve. This article examines the diagnostic performance and clinical value of capsule endoscopy in comparison with conventional endoscopic methods, focusing on accuracy, safety, and practical applicability across different gastrointestinal conditions.

Comparative Diagnostic Performance of Capsule Endoscopy and Conventional Endoscopy

Assessing the diagnostic performance of capsule endoscopy (CE) relative to conventional endoscopy (encompassing EGD, colonoscopy, and related procedures) requires a nuanced understanding of each modality’s clinical strengths, limitations, and suitability for specific gastrointestinal (GI) conditions. While conventional endoscopy remains the gold standard for mucosal biopsy, targeted visualization, and therapeutic intervention, CE demonstrates competitive—and in some cases superior—diagnostic yield in evaluating mid-small bowel pathology, particularly when conventional access is limited.

Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding and Small Bowel Evaluation

One of CE’s most validated indications is the investigation of obscure GI bleeding (OGIB), defined as bleeding that persists or recurs after negative esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy. The diagnostic yield of CE for OGIB has been reported to range from 32% to 83%, varying by whether bleeding is overt or occult and by the timing of capsule deployment (1, 2). In comparative trials, CE consistently outperforms both push enteroscopy and radiologic studies for small bowel visualization.

A meta-analysis by Teshima et al. (2011) found that CE had a significantly higher diagnostic yield (63%) than push enteroscopy (28%) for clinically significant findings. This meta-analysis also indicated similar diagnostic yields between CE (62%) and double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) (56%) for OGIB (3). CE offers unparalleled mucosal visualization of the small intestine—an area largely inaccessible by standard endoscopes—and thus serves as a first-line modality for OGIB and suspected small bowel Crohn’s disease.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Crohn’s Disease

In suspected Crohn’s disease, CE provides excellent mucosal detail, particularly for early or proximal small bowel involvement. It can detect aphthous ulcers, mucosal breaks, and skip lesions not visible on ileocolonoscopy or cross-sectional imaging.

Meta-analyses have demonstrated CE’s high diagnostic accuracy for Crohn’s disease, with a pooled sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 88% (4, 5).

While conventional colonoscopy with ileoscopy remains essential for histologic confirmation and extent mapping, CE is particularly valuable when:

- Ileocolonoscopy is non-diagnostic.

- Deep small bowel involvement is suspected.

- The patient is unfit for invasive procedures.

CE should not replace tissue diagnosis but plays a crucial adjunct role, especially in cases of early or patchy small bowel disease.

Celiac Disease

CE may detect features such as villous atrophy, scalloping, and mosaic mucosa in patients unable or unwilling to undergo conventional biopsy. However, conventional endoscopy with duodenal biopsy remains the diagnostic gold standard for celiac disease.

In select cases (e.g., pediatric patients, those refusing invasive testing), CE offers reasonable sensitivity (∼89%) for celiac-associated mucosal changes and a specificity of 95% (6, 7). Nevertheless, its interpretation is operator-dependent and inherently lacks histological confirmation.

Colorectal Cancer and Polyp Detection

Conventional colonoscopy remains the benchmark modality for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening due to its combined diagnostic and therapeutic capability. However, second-generation colon capsule endoscopy (CCE-2) shows promising results in selected populations.

A meta-analysis by Spada et al. (2016) reported that CCE-2 detected polyps ≥6 mm with an 86% sensitivity and 88.1% specificity. Its high negative predictive value (NPV) of >95% supports its use as a triage tool for low-risk patients or in cases of incomplete colonoscopy (8, 9).

CCE is particularly useful in:

- Patients with incomplete colonoscopy.

- Individuals who refuse sedation or invasive procedures.

- Elderly or anticoagulated patients at increased procedural risk.

Nonetheless, polyps detected by CCE still necessitate follow-up colonoscopy for removal, thereby limiting CCE’s role to detection and triage.

Esophageal Disorders: Barrett’s and Varices

For Barrett’s esophagus, CE has shown moderate sensitivity (∼78%) and high specificity (∼90%) in screening studies (10, 11). However, its inability to perform biopsy or dysplasia surveillance makes EGD the established standard of care.

In portal hypertension, esophageal capsule endoscopy (ECE) has demonstrated high accuracy in detecting esophageal varices. Studies report sensitivity and specificity exceeding 85% compared to EGD (12, 13). ECE may therefore serve as a valuable screening tool in cirrhotic patients unwilling or unable to undergo standard endoscopy.

Diagnostic Limitations and False Negatives

While CE’s overall diagnostic sensitivity is high under ideal conditions, it may be compromised by factors such as:

- Poor bowel preparation.

- Rapid transit.

- Lesion orientation.

- Non-visualized segments.

- Capsule retention or incomplete studies.

In contrast, conventional endoscopy allows real-time visualization, suction, irrigation, and the ability to manipulate folds, which significantly improves diagnostic precision—particularly for subtle or flat lesions.

CE, relying on passive image acquisition, is inherently more susceptible to missed or suboptimally captured pathology. However, the integration of AI-based triage tools has progressively narrowed this performance gap.

| Condition | Capsule Endoscopy | Conventional Endoscopy |

| Obscure GI Bleeding | ✅ Superior for small bowel yield | ✅ EGD/Colonoscopy for first-line assessment |

| Crohn’s Disease | ✅ Sensitive for small bowel involvement | ✅ Required for biopsy and full extent mapping |

| Celiac Disease | ⚠️ Supportive; lacks biopsy capability | ✅ Gold standard via duodenal biopsy |

| Colorectal Cancer | ✅ Useful for triage/screening | ✅ Gold standard with concurrent polypectomy |

| Esophageal Varices | ✅ Accurate in cirrhotics for screening | ✅ Allows band ligation and therapeutic intervention |

| Barrett’s Esophagus | ⚠️ Detects columnar lining; no biopsy | ✅ Allows dysplasia surveillance and biopsy |

| Small Bowel Tumors | ✅ Early detection and localization | ✅ Essential for tissue diagnosis and therapy |

Capsule endoscopy demonstrates comparable—and sometimes superior—diagnostic yield in selected contexts, such as obscure small bowel bleeding, non-stricturing Crohn’s disease, and for evaluating incomplete colonoscopies. However, its passive nature and absence of interventional capabilities inherently restrict its role to diagnostic complementarity rather than replacement. Clinical judgment remains paramount in modality selection, with decisions guided by patient condition, the specific anatomical target, and the need for immediate therapeutic interventions.

Patient Experience and Safety

In contemporary clinical practice, patient experience is recognized not merely as a secondary outcome but as a central pillar of diagnostic strategy, particularly in preventive screening, chronic disease surveillance, and ambulatory care. The decision to pursue capsule versus conventional endoscopy often hinges not only on clinical utility but also on factors such as patient comfort, risk tolerance, preparation burden, and procedural anxiety—particularly in vulnerable groups such as the elderly, children, or those with multiple comorbidities.

Procedure Tolerance and Comfort

One of the most frequently cited advantages of capsule endoscopy (CE) is its superior patient tolerability. CE is non-invasive, does not require sedation, and is conducted on an ambulatory basis, making it significantly less distressing for most patients.

Multiple studies have demonstrated high acceptance rates for CE. In a prospective multicenter survey by Spada et al. (2016), over 95% of patients rated capsule endoscopy as more acceptable than conventional endoscopy and expressed willingness to repeat the procedure if needed (8).

Unlike conventional endoscopy, CE involves no oropharyngeal instrumentation, no need for intravenous (IV) access, and no recovery time, significantly reducing patient apprehension. In contrast, conventional endoscopy requires sedation, bowel preparation, and sometimes intravenous anesthesia, often necessitating an escort and post-procedure recovery. These requirements can deter screening adherence, especially for asymptomatic individuals.

Sedation Risk and Special Populations

Sedation-related complications remain a significant concern with conventional endoscopy, particularly in geriatric and cardiopulmonary-compromised patients. A large retrospective cohort study by Mahmud et al. (2021) reported a 3.6-fold increased risk of sedation-related adverse events (e.g., hypoxia, hypotension, arrhythmia) in patients aged ≥75 years compared to younger cohorts.

In contrast, CE entirely avoids these risks. It has demonstrated safety and feasibility in:

- Pediatric patients, including children as young as 2 years with suspected small bowel bleeding or IBD (14).

- Elderly and frail individuals, where procedural sedation may be contraindicated.

- Patients with neurocognitive impairment, where cooperation with traditional procedures is limited.

CE thus serves as an ideal first-line or alternative modality in populations where procedural risk, fear, or frailty would otherwise limit access to diagnostic imaging.

Bowel Preparation and Patient Burden

While capsule endoscopy is less invasive, it is not without preparation requirements. For small bowel CE, a clear liquid diet and overnight fasting are typically sufficient, though some centers recommend low-volume bowel preparation or prokinetics to improve mucosal visualization.

Colon capsule endoscopy (CCE), however, requires a preparation regimen similar in intensity to conventional colonoscopy, including:

- 2–4 liters of polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution.

- Booster agents such as sodium phosphate or magnesium citrate.

Although preparation quality remains a major determinant of CE diagnostic yield, studies have shown patients tolerate the capsule procedure itself better than conventional alternatives, even with equivalent preparation burdens (15).

Safety Profile and Adverse Events

Capsule Endoscopy (CE)

- Serious adverse events are rare.

- The most significant risk is capsule retention, occurring in approximately 1–2% of all patients.

- Retention is more common in patients with Crohn’s disease, strictures, or tumors.

- No perforation, no bleeding, and no sedation-related events have been reported in large case series.

Capsule retention is usually asymptomatic and detected upon failure to visualize capsule passage. In most cases, the capsule can be retrieved via:

- Enteroscopy, if feasible.

- Surgery, in rare cases with obstruction.

The use of a patency capsule before CE in high-risk individuals can mitigate this risk.

Conventional Endoscopy

- Perforation risk: Approximately 0.03% for EGD and up to 0.1–0.3% for colonoscopy (16).

- Bleeding risk increases with polypectomy or biopsy.

- Sedation complications: These include respiratory depression, bradycardia, and hypotension.

- Infection transmission risk is low but non-zero, especially with inadequate scope reprocessing.

Thus, while conventional endoscopy enables immediate intervention, its safety profile is more invasive, and careful risk stratification is necessary prior to procedural scheduling.

Adherence and Long-Term Acceptance

Population-level studies suggest that fear of discomfort, embarrassment, and sedation are major barriers to screening colonoscopy, particularly for colorectal cancer prevention. Capsule-based screening could significantly increase adherence in:

- Younger patients with high procedural anxiety.

- Rural populations where hospital-based endoscopy units are limited.

- Cultural contexts with low tolerance for invasive procedures.

A randomized trial by Kroijer et al. (2022) found that offering CCE increased screening uptake by 17% compared to conventional invitation for colonoscopy.

| Factor | Capsule Endoscopy | Conventional Endoscopy |

| Invasiveness | Non-invasive | Invasive |

| Sedation Required | ❌ No | ✅ Yes (usually IV or MAC) |

| Tolerability | High | Moderate to low |

| Procedure Duration | Short (swallow + wear recorder) | 20–45 min + recovery |

| Recovery Time | None | ≥2 hours |

| Complication Risk | Low (retention ∼1–2%) | Moderate (perforation, sedation risk) |

| Preferred for | Elderly, children, frail, outpatient | Biopsy, intervention, therapeutic cases |

| Patient Adherence | High | Lower in asymptomatic/screening populations |

Integration and Future Outlook

Gastrointestinal endoscopy is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by parallel advancements in both conventional endoscopic systems and capsule-based platforms. While conventional endoscopy remains indispensable for its real-time control, interventional capability, and histopathological precision, capsule endoscopy (CE) is increasingly shaping the future of non-invasive, decentralized diagnostics—particularly in areas of the GI tract where traditional tools have limited access.

The relationship between CE and conventional modalities is therefore not competitive but complementary. This paradigm of procedural convergence—where the strengths of one modality compensate for the limitations of the other—is becoming increasingly central to modern GI diagnostic algorithms.

Toward a Hybrid Diagnostic Strategy

Emerging evidence suggests that the most effective diagnostic strategies are not those that favor one modality over the other, but rather those that integrate both based on patient factors, clinical indications, and healthcare resource availability. For example:

- In obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, CE offers a first-line diagnostic approach for small bowel lesions, often followed by conventional endoscopy (e.g., double-balloon enteroscopy) for targeted therapy.

- In colorectal cancer screening, CE can serve as a triage tool or an alternative when colonoscopy is incomplete or declined, thereby improving adherence without sacrificing diagnostic yield.

- In Crohn’s disease, CE allows early detection of proximal small bowel inflammation, while colonoscopy provides tissue diagnosis and therapeutic surveillance.

This integrated approach not only enhances diagnostic completeness but also improves patient stratification, cost-efficiency, and adherence to screening and surveillance programs.

Technological Convergence and AI-Driven Personalization

The future of GI diagnostics lies in the fusion of AI, robotics, and biosensing into both conventional and capsule-based platforms. Capsule endoscopy is transitioning from passive observation to smart diagnostic ecosystems, capable of:

- Autonomous navigation and control.

- Real-time lesion detection using AI.

- Onboard sensors for chemical, pH, and pressure analysis.

- Therapeutic delivery, including biopsy and cautery tools.

Meanwhile, conventional endoscopy is being augmented by:

- AI overlays that assist during live colonoscopy procedures.

- Robotic-assisted scopes with enhanced precision.

- Augmented reality navigation and digital mucosal mapping.

Such technologies will lead to precision endoscopy—highly personalized, low-risk, and data-rich procedures tailored to individual risk profiles, anatomy, and disease patterns.

Implementation in Global Screening and Remote Care

Capsule endoscopy’s portability, lack of sedation, and minimal infrastructure requirements make it ideally suited for:

- Community-based cancer screening programs.

- Pediatric or geriatric care in rural areas.

- Outpatient chronic disease monitoring.

- Post-pandemic decentralized diagnostics, where contactless or at-home testing is preferred.

In countries with limited access to trained endoscopists or procedural infrastructure, CE may democratize high-quality GI imaging through:

- Cloud-based data transmission.

- Remote AI triage.

- Asynchronous specialist interpretation.

These advantages align CE with future models of tele-endoscopy and AI-supported diagnostics within national healthcare systems.

Future Clinical Questions

Several pivotal questions remain as CE and conventional endoscopy continue to evolve:

- Can capsule endoscopy safely replace colonoscopy in average-risk CRC screening?

- Will robotic capsules allow therapeutic functions such as biopsy or polypectomy in the next decade?

- How will AI algorithms be regulated, validated, and reimbursed in real-time clinical workflows?

- What are the ethical implications of autonomous capsule diagnostics in asymptomatic patients?

Answering these questions will require robust clinical trials, interdisciplinary collaboration, and transparent guideline development by gastroenterological societies and regulatory bodies.

In conclusion capsule and conventional endoscopy are no longer isolated domains but rather parts of a converging landscape of smart, flexible, and minimally invasive gastrointestinal diagnostics. The next generation of tools will likely combine the real-time control of conventional systems with the autonomous intelligence and safety profile of capsule platforms, ushering in an era of adaptive, patient-centered endoscopy.

By understanding the complementary roles and evolving capabilities of each modality, clinicians and health systems can make evidence-informed decisions that maximize diagnostic yield, minimize procedural risk, and improve long-term outcomes in gastrointestinal care.

REFERENCES

- Pennazio, M., Santucci, R., Rondonotti, E., Abbiati, C., Beccari, G., Rossini, F. P., & De Franchis, R. (2004). Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology, 126(3), 643–653. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.057

- Sun, Y., Meng, R., Zhang, J., Hu, S., Wang, Z., & Chen, H. (2016). Diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: A meta-analysis. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 61(4), 963-971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-015-3974-9

- Teshima, C., Kuipers, E. J., van Zanten, S. V., & Mensink, P. B. (2011). Double balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: an updated meta-analysis. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 26(4), 796-801. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06559.x

- Lian, L., Zhu, Y., Wang, B., Zhang, P., & Li, S. (2023). Diagnostic value of colon capsule endoscopy for inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Medicine, 10, 1113279. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1113279

- Triester, S. L., > with others. (2006). Capsule endoscopy versus other modalities for the diagnosis of small bowel Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 4(8), 1007-1015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2006.06.002

- Rondonotti, E., Villa, F., Saladino, V., & de Franchis, R. (2007). Capsule endoscopy in celiac disease. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 22(Suppl 1), S19-S23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05059.x

- Hopper, A. D., Hadjivassiliou, M., Sheridan, A., Papaioannou, S., Gibson, B. S., Sanders, D. S. (2007). Capsule endoscopy in adult coeliac disease: a prospective study. Digestive and Liver Disease, 39(12), 1098-1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2007.07.009

- Spada, C., Hassan, C., Galmiche, J. P., Dray, X., Polese, L., Mangiavillano, B., … & Costamagna, G. (2016). Colon capsule endoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy, 48(4), 370-384. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-102558

- De Franchis, R., & The Baveno VI Faculty. (2020). Revisiting the Baveno VI consensus: Update for the management of portal hypertension in cirrhotic patients. Journal of Hepatology, 72(1), 162-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.08.026

- Eliakim, R., Sharma, V. K., & Shor, H. B. (2009). A prospective, multicenter study of esophageal capsule endoscopy for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 69(4), 793-797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2008.07.042

- Sharma, P., Shaheen, N. J., Iyer, P. G., & Fennerty, M. B. (2007). AGA Institute Medical Position Statement on the Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology, 133(1), 346-351. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.045

- Lapalus, M. G., D’Halluin, P. N., Perarnau, J. M., Giraud, F., Metman, E. H., & Vanbiervliet, G. (2006). Esophageal capsule endoscopy vs. esophagogastroduodenoscopy for screening of esophageal varices. Gastroenterology, 131(2), 405-412. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.012

- Le Floch, C., Shiha, A., & da Costa, A. C. (2025). Biosensing and Functional Diagnostics in GI: A New Era.

- Oliva, S., Di Nardo, G., Dall’Oglio, L., Civitelli, F., & de Angelis, P. (2014). Capsule endoscopy in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a multicenter study. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 58(1), 105-110. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182a472a1

- Spada, C., Hassan, C., Marmo, R., D’Amico, F., & Sgalla, R. M. (2021). Second-generation colon capsule endoscopy for colorectal cancer screening. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 6(12), 1073-1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00345-4

- Waye, J. D., Thirumurthi, S., & Giesler, D. (2000). Management of complications of colonoscopy. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America, 10(3), 543-564. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1052-5157(18)30062-X

- Kroijer, R., Jørgensen, M. C., Krarup, L. H., & Riis, L. B. (2022). Effectiveness of colon capsule endoscopy as primary colorectal cancer screening strategy in a population-based setting: a randomised trial. Gut, 71(5), 903-911. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325251