Non-Invasive Mechanical Ventilation (NIV) plays a central role in modern respiratory support strategies. By delivering positive airway pressure without the need for endotracheal intubation, NIV enhances gas exchange, decreases the work of breathing, and helps prevent complications associated with invasive mechanical ventilation. Ongoing advances in ventilator technology, interface development, and clinical practice have broadened its application across a wide spectrum of acute and chronic respiratory disorders. Today, NIV is recommended in international clinical guidelines for selected forms of respiratory failure, particularly hypercapnic respiratory failure and acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

What Is Non-Invasive Mechanical Ventilation (NIV)?

Non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) has become an integral component of contemporary respiratory care, offering ventilatory support without the need for an artificial airway. By delivering positive pressure ventilation through an external interface, NIV aims to improve gas exchange, reduce the work of breathing, and alleviate respiratory distress while avoiding complications associated with invasive mechanical ventilation, such as ventilator-associated pneumonia, airway trauma, and the need for sedation (1–3). Over the past several decades, advances in ventilator technology, interface design, and clinical understanding have expanded the role of NIV across a broad range of acute and chronic respiratory conditions (1,3).

The clinical adoption of NIV has been driven by a growing body of evidence demonstrating its effectiveness in selected patient populations, particularly in the management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cardiogenic pulmonary edema (4,7). In these settings, NIV has been associated with reduced rates of endotracheal intubation, shorter hospital stays, and improved patient tolerance compared with conventional invasive ventilation strategies (4–7). As a result, NIV is now recommended by multiple international guidelines as a first-line ventilatory intervention in specific clinical scenarios (6,8). Nevertheless, the success of NIV is highly dependent on appropriate patient selection, timely initiation, and the performance characteristics of the ventilatory device and interface used (6).

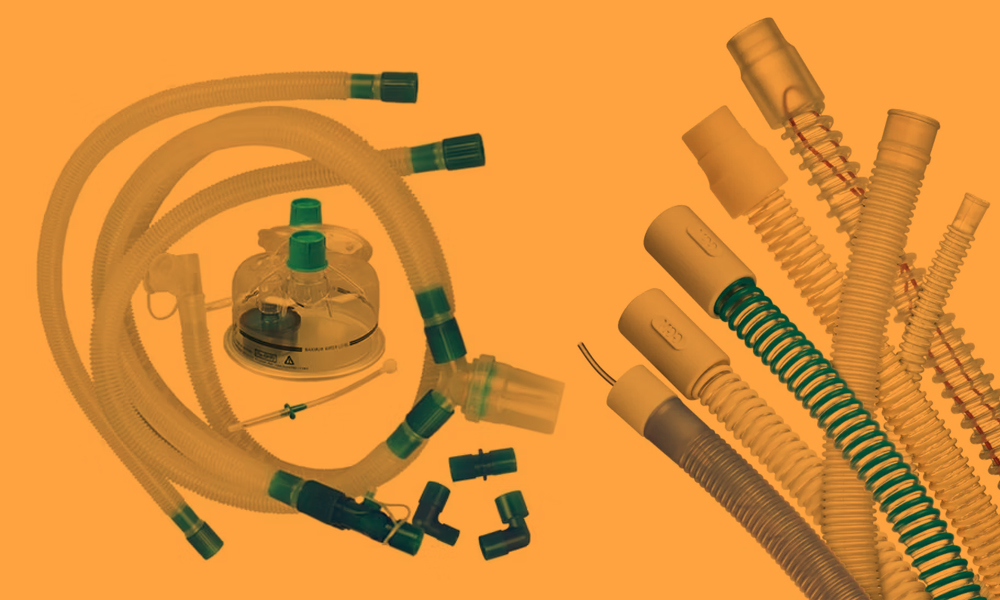

From a technological perspective, NIV presents unique challenges that distinguish it from invasive mechanical ventilation. The presence of intentional and unintentional leaks, variability in patient respiratory effort, and the need for patient–ventilator synchrony require ventilators specifically designed or adapted for non-invasive application (9–11). Over time, manufacturers have developed dedicated NIV ventilators as well as advanced non-invasive modes within intensive care unit (ICU) ventilators, incorporating features such as leak compensation algorithms, sensitive triggering mechanisms, and adaptive pressure support (9,10). These technological developments have played a critical role in improving the feasibility and tolerability of NIV in both acute care and long-term settings (10).

In parallel with ventilator evolution, the development of patient interfaces has significantly influenced NIV outcomes. A wide range of interfaces—including nasal masks, oronasal masks, full-face masks, and helmet systems—are now available, each with distinct advantages and limitations related to comfort, seal integrity, dead space, and risk of pressure-related skin injury (12–14). Interface selection is a key determinant of NIV success and remains an area of active clinical and engineering interest (12,13). The increasing diversity of interfaces reflects the need to tailor NIV delivery to individual patient anatomy, clinical condition, and tolerance (14).

Despite its widespread use, NIV is not universally appropriate and may be associated with treatment failure if applied outside well-defined indications or in the presence of contraindications such as impaired airway protection, severe hemodynamic instability, or altered mental status (5,6). Delayed recognition of NIV failure and postponement of invasive ventilation can adversely affect patient outcomes (5,15). Consequently, clinicians must balance the potential benefits of NIV against its limitations, guided by clinical assessment, physiological monitoring, and an understanding of device performance (6). For regulators and biomedical engineers, these considerations underscore the importance of safety features, alarm systems, and standardized performance requirements in NIV-capable ventilators (9,10).

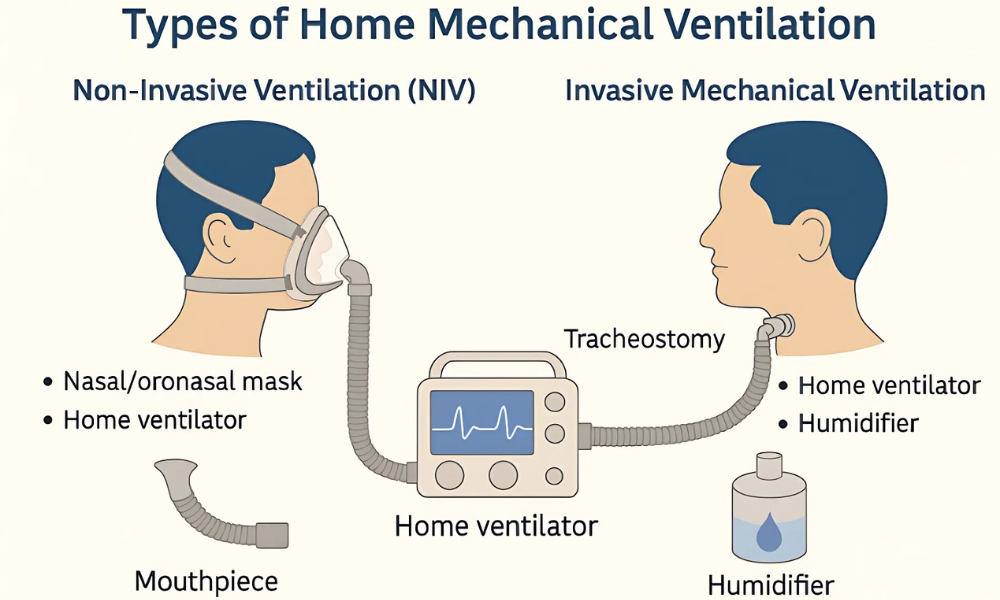

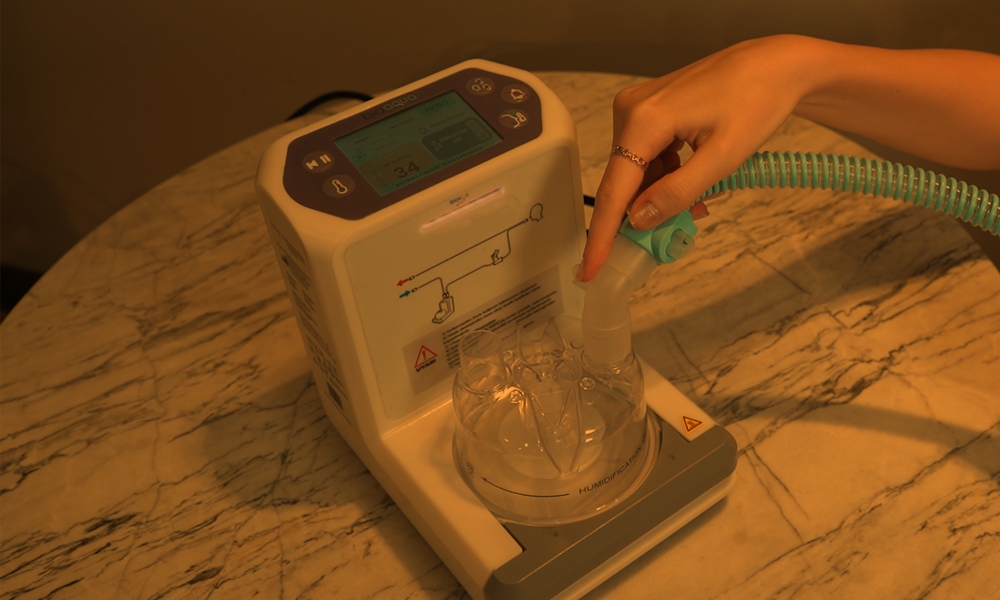

The expanding role of NIV beyond the ICU into emergency departments, general wards, and home care environments has further increased the relevance of device design and usability (10,13). Portable ventilators, home NIV systems, and hybrid devices intended for both acute and chronic use have introduced new considerations related to reliability, monitoring capabilities, and regulatory oversight (10,13). In this context, a clear understanding of the clinical indications for NIV and the technologies that support its delivery is essential for informed clinical practice, device development, and regulatory evaluation.

The objective of this narrative review is to describe the clinical use of non-invasive mechanical ventilation, with a particular focus on its established and emerging indications and the ventilator technologies that enable its application. Rather than providing a systematic evaluation of clinical outcomes, this review synthesizes key concepts from the existing literature to offer a descriptive overview of NIV physiology and clinical indications relevant to modern practice. By integrating clinical and engineering perspectives, this review aims to support clinicians, biomedical engineers, and regulatory professionals in understanding the current landscape of non-invasive mechanical ventilation.

Physiological Principles of Non-Invasive Mechanical Ventilation

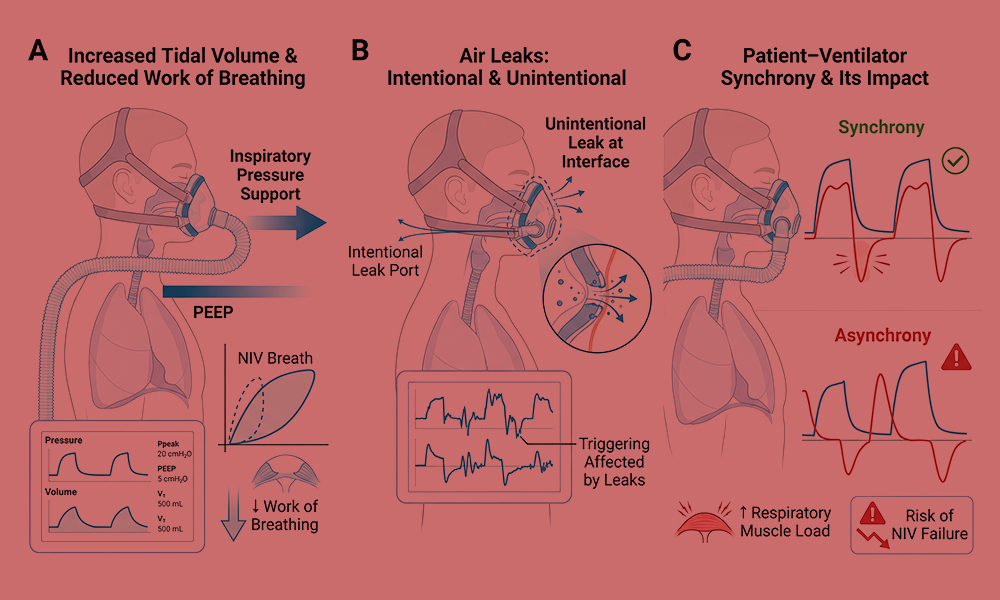

Non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) supports the respiratory system by delivering positive airway pressure through an external interface, thereby assisting or replacing spontaneous breathing without the placement of an endotracheal tube. The primary physiological objectives of NIV are to improve alveolar ventilation, enhance gas exchange, reduce the work of breathing, and alleviate respiratory muscle fatigue (1,3). These effects are achieved through the application of positive pressure during inspiration, expiration, or both, depending on the ventilation mode used.

Effects on Respiratory Mechanics and Gas Exchange

In patients with acute or chronic respiratory failure, increased airway resistance, reduced lung compliance, or respiratory muscle dysfunction may lead to hypoventilation and gas exchange abnormalities. By providing inspiratory pressure support, NIV augments tidal volume and minute ventilation, leading to a reduction in arterial carbon dioxide tension (PaCO₂) and improvement in respiratory acidosis, particularly in hypercapnic respiratory failure such as acute exacerbations of COPD (4,6). The unloading of inspiratory muscles reduces diaphragmatic effort and oxygen consumption, which contributes to improved respiratory efficiency and patient comfort (1,3).

The application of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), either alone as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or in combination with inspiratory pressure support, increases functional residual capacity and prevents alveolar collapse at end expiration (2,7). This mechanism is particularly relevant in conditions characterized by alveolar flooding or atelectasis, such as cardiogenic pulmonary edema, where PEEP improves oxygenation by enhancing ventilation–perfusion matching and reducing intrapulmonary shunt (7).

Cardiovascular Effects of NIV

The application of positive airway pressure during NIV can have significant cardiovascular effects. By increasing intrathoracic pressure, NIV reduces venous return and left ventricular preload while simultaneously decreasing left ventricular afterload (2,7). These mechanisms are particularly beneficial in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema, where NIV improves cardiac performance and pulmonary congestion while enhancing oxygenation (7).

However, in patients with hypovolemia or hemodynamic instability, excessive airway pressures may adversely affect cardiac output. Understanding these physiological interactions is essential for safe NIV application and informs ventilator pressure limits, alarm thresholds, and monitoring requirements from both clinical and regulatory perspectives (6,9).

Determinants of NIV Success and Failure

The physiological response to NIV is influenced by multiple factors, including disease severity, respiratory drive, interface tolerance, and ventilator performance. Early improvements in respiratory rate, gas exchange, and patient comfort are generally associated with NIV success, whereas persistent tachypnea, worsening gas exchange, or increased work of breathing may signal impending failure (5,15). From a physiological standpoint, failure to adequately unload respiratory muscles or correct gas exchange abnormalities may necessitate escalation to invasive mechanical ventilation.

These considerations highlight the importance of continuous physiological monitoring during NIV and reinforce the need for ventilators equipped with reliable monitoring systems, alarms, and safety features. For biomedical engineers and regulators, an understanding of these physiological principles is essential when evaluating device performance, usability, and clinical risk.

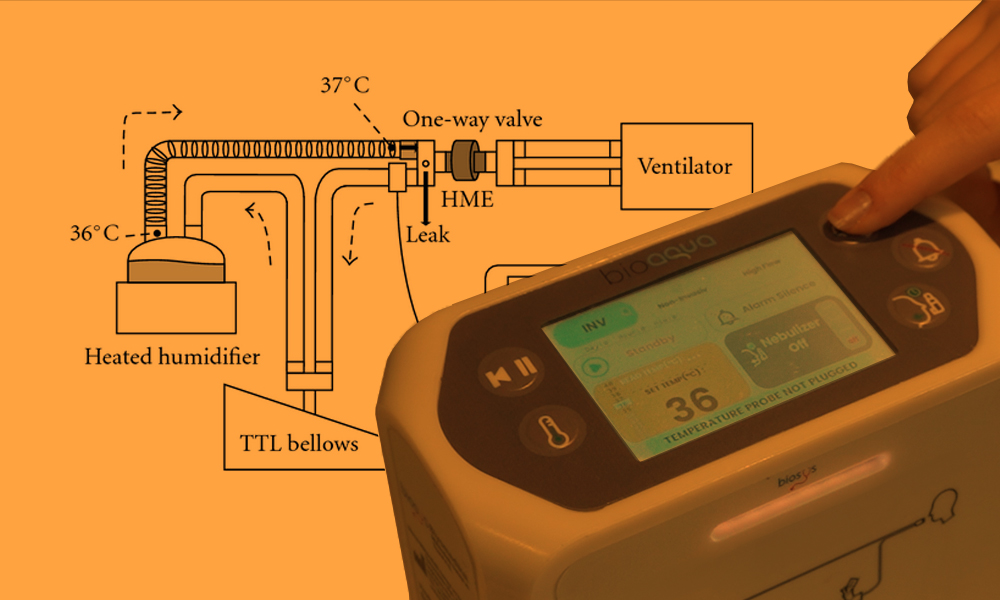

Figure 1. Physiological principles of non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV).

(A) Application of inspiratory pressure support and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) during NIV augments tidal volume and reduces the work of breathing compared with spontaneous breathing. (B) Air leaks are inherent to NIV and may occur intentionally through leak ports or unintentionally at the interface–skin junction, influencing effective pressure delivery and ventilator triggering. (C) Patient–ventilator synchrony depends on accurate detection of patient inspiratory effort and appropriate cycling of ventilator support; poor synchrony may increase respiratory muscle load and contribute to NIV failure.

| Physiological goal | Underlying mechanism | Ventilator feature or technology | Clinical relevance |

| Reduce work of breathing | Inspiratory muscle unloading | Pressure support ventilation | Decreases respiratory muscle fatigue |

| Improve alveolar ventilation | Increased tidal volume | Adjustable inspiratory pressure | Reduces hypercapnia |

| Prevent alveolar collapse | Increased functional residual capacity | Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) | Improves oxygenation |

| Improve patient–ventilator synchrony | Accurate detection of patient effort | Flow or pressure triggering algorithms | Enhances comfort and tolerance |

| Compensate for air leaks | Maintenance of target pressure | Leak compensation algorithms | Prevents loss of ventilatory support |

| Minimize CO₂ rebreathing | Effective washout of exhaled gas | Intentional leak ports or exhalation valves | Maintains ventilation efficiency |

| Adapt to variable respiratory demand | Dynamic adjustment of support | Adaptive or volume-assured pressure modes | Improves stability across conditions |

| Enhance patient comfort | Reduced interface pressure and noise | Interface design and humidification | Increases NIV adherence |

| Ensure patient safety | Detection of abnormal conditions | Alarms and monitoring systems | Reduces risk of adverse events |

Clinical Indications for Non-Invasive Mechanical Ventilation

Non-invasive mechanical ventilation is indicated in selected clinical conditions characterized by acute or chronic respiratory failure, where ventilatory support can be provided safely and effectively without the need for endotracheal intubation. The appropriateness of NIV depends on the underlying pathophysiology, severity of respiratory failure, patient cooperation, and the absence of contraindications such as impaired airway protection or severe hemodynamic instability (1,6). When applied within established indications, NIV may reduce the need for invasive mechanical ventilation and its associated complications (1,4).

Acute Exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD)

Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) represents the most well-established and evidence-supported indication for NIV. Exacerbations are frequently associated with increased airway resistance, dynamic hyperinflation, respiratory muscle fatigue, and hypercapnic respiratory acidosis. NIV improves alveolar ventilation by augmenting tidal volume and reducing inspiratory muscle load, leading to rapid reductions in arterial carbon dioxide tension and correction of acidosis (3,4).

Multiple randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews have demonstrated that NIV in AECOPD reduces rates of endotracheal intubation, hospital mortality, and length of hospital stay compared with standard medical therapy alone (4,16,17). The early application of NIV, including use outside the intensive care unit in appropriately selected patients, has also been shown to improve clinical outcomes (17). Consequently, international clinical practice guidelines recommend NIV as first-line ventilatory support in patients with AECOPD presenting with moderate to severe respiratory acidosis and increased work of breathing, provided no contraindications are present (6,8).

Acute Cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema

NIV is strongly indicated in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema, where respiratory failure results primarily from alveolar flooding and reduced lung compliance rather than ventilatory pump failure. The application of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bilevel NIV increases functional residual capacity, improves oxygenation, and reduces both left ventricular preload and afterload through increased intrathoracic pressure (2,7).

Randomized trials and meta-analyses have demonstrated that NIV leads to rapid improvement in respiratory distress and gas exchange and reduces the need for endotracheal intubation compared with conventional oxygen therapy (7,18). Both CPAP and bilevel NIV are considered acceptable modalities, with device selection often guided by clinical severity, hemodynamic status, and local expertise (6,18).

Hypoxemic Acute Respiratory Failure

The use of NIV in hypoxemic acute respiratory failure, including pneumonia and early acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), remains controversial. In these conditions, severe ventilation–perfusion mismatch, reduced lung compliance, and high inspiratory demand may limit the effectiveness of NIV and increase the risk of treatment failure (6,15).

Early studies suggested potential benefits of NIV in carefully selected patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure, particularly in terms of avoiding intubation (19). However, subsequent evidence has highlighted high failure rates and worse outcomes when intubation is delayed in patients who do not respond promptly to NIV (15). As a result, current guidelines recommend cautious use of NIV in this population, with close monitoring and a low threshold for escalation to invasive ventilation (6). The emergence of alternative non-invasive oxygenation strategies, such as high-flow nasal oxygen, has further refined patient selection in hypoxemic respiratory failure (20).

Post-Extubation Respiratory Failure and Weaning

NIV has been studied both as a preventive strategy following planned extubation and as a treatment for established post-extubation respiratory failure. Prophylactic application of NIV in selected high-risk patients—such as those with underlying COPD or chronic hypercapnia—has been shown to reduce the incidence of respiratory failure and the need for reintubation (21).

In contrast, the use of NIV as a rescue therapy once post-extubation respiratory failure is established has been associated with increased mortality in some studies, likely due to delayed reintubation (5). Current guidelines therefore recommend selective use of NIV in this setting and emphasize careful patient selection and close clinical monitoring (6).

Neuromuscular Diseases and Chest Wall Disorders

Neuromuscular diseases and chest wall disorders are characterized by chronic ventilatory failure due to respiratory muscle weakness and reduced thoracic compliance. NIV is widely used in both acute decompensations and long-term management to improve alveolar ventilation, alleviate symptoms of hypoventilation, and reduce the burden on respiratory muscles (1,3).

Long-term NIV has been shown to improve gas exchange, sleep quality, and survival in selected neuromuscular conditions, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (22,23). Device features such as sensitive triggering, volume-assured pressure support, and comfortable interfaces are particularly important in this population, where long-term adherence is essential (10,22).

Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome

Obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) is characterized by chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure resulting from obesity-related reductions in respiratory system compliance and ventilatory drive. NIV is indicated in patients with OHS who exhibit persistent daytime hypercapnia, particularly when CPAP therapy alone is insufficient (6,24).

NIV improves ventilation by augmenting tidal volume and reducing respiratory muscle workload, leading to sustained improvements in gas exchange and sleep-related breathing disturbances. Long-term NIV has also been associated with improved quality of life and reduced healthcare utilization in this population (24). Ventilator adaptability and effective leak compensation are key technical considerations in patients with OHS (10).

Palliative and End-of-Life Use of NIV

NIV may be used as a supportive or palliative intervention in patients with advanced respiratory disease who decline invasive mechanical ventilation or for whom intubation is not appropriate. In this context, the primary goals are relief of dyspnea and improvement of comfort rather than correction of physiological abnormalities (1,25).

Studies have shown that NIV can reduce dyspnea and respiratory distress in selected end-of-life patients, although careful attention must be paid to patient tolerance, goals of care, and ethical considerations (25). Device usability, interface comfort, and noise reduction are particularly relevant when NIV is applied in palliative settings or outside the ICU environment (13,25).

References

- Nava S, Hill N. Non-invasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure. Lancet. 2009;374(9685):250–9.

- Brochard L, Slutsky A, Pesenti A. Mechanical ventilation to minimize progression of lung injury in acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(4):438–42.

- Mehta S, Hill NS. Noninvasive ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(2):540–77.

- Brochard L, Mancebo J, Wysocki M, et al. Noninvasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(13):817–22.

- Esteban A, Frutos-Vivar F, Ferguson ND, et al. Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation for respiratory failure after extubation. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(24):2452–60.

- Rochwerg B, Brochard L, Elliott MW, et al. Official ERS/ATS clinical practice guidelines: noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2):1602426.

- Vital FM, Ladeira MT, Atallah ÁN. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD005351.

- British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee. Non-invasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure. Thorax. 2002;57(3):192–211.

- Vignaux L, Tassaux D, Jolliet P. Performance of noninvasive ventilation algorithms. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(12):2053–60.

- Carlucci A, Richard JC, Wysocki M, et al. Noninvasive versus conventional mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(4):874–80.

- Thille AW, Rodriguez P, Cabello B, et al. Patient–ventilator asynchrony during noninvasive ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(10):1515–22.

- Girault C, Briel A, Hellot MF, et al. Interface strategy during noninvasive positive pressure ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(2):259–65.

- Crimi C, Noto A, Princi P, et al. A European survey of noninvasive ventilation practices. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(2):362–9.

- Antonelli M, Conti G, Pelosi P, et al. New treatment of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: helmet NIV. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(12):1701–7.

- Carrillo A, Gonzalez-Diaz G, Ferrer M, et al. Non-invasive ventilation in community-acquired pneumonia and severe acute respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(3):458–66.

- Lightowler JV, Wedzicha JA, Elliott MW, Ram FSF. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation to treat respiratory failure resulting from exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(1):CD004104.

- Plant PK, Owen JL, Elliott MW. Early use of non-invasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on general respiratory wards. Lancet. 2000;355(9219):1931–1935.

- Gray A, Goodacre S, Newby DE, et al. Noninvasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(2):142–151.

- Antonelli M, Conti G, Rocco M, et al. A comparison of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation and conventional mechanical ventilation in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(7):429–435.

- Frat JP, Thille AW, Mercat A, et al. High-flow oxygen through nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(23):2185–2196.

(Useful comparator — reviewers like this) - Ferrer M, Valencia M, Nicolas JM, et al. Early noninvasive ventilation averts extubation failure in patients at risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(2):164–170.

- Simonds AK. Home ventilation. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(47 Suppl):38s–46s.

- Bourke SC, Gibson GJ. Noninvasive ventilation in ALS. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(10):607–615.

- Masa JF, Pépin JL, Borel JC, et al. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28(151):180097.

- Nava S, Ferrer M, Esquinas A, et al. Palliative use of non-invasive ventilation in end-of-life patients. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(10):1876–1885.